Page 226-229, Press Photography in the Context of National Socialist Propaganda Means in the Reichsgau Wartheland

Page 226-229 > access to source at the UDK > Teilband 1 > Link

Translation of contents with the friendly permission of Verlag Dr. Kovač Hamburg.

Author information: Miriam Y. Arani

URN: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:kobv:b170-17233

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25624/kuenste-1723

ISBN: 978-3-8300-3005-8

Publisher: Verlag Dr. Kovač

Place of publishing: Hamburg

Document type: Book (Monograph)

Language: German

Year of completion: 2008

Publishing Institution: Universität der Künste Berlin

Date of release: 23.02.2022

GND keyword: Wartheland; Poland – people; Germans; photography; self-image; foreign image; Wartheland; Polen – Volk; Deutsche; Fotografie; Selbstbild; Fremdbild

Page number: 1014

License (German): No license – copyright protection

From Chapter III: National Socialist Press – Reichsgau Wartheland

[…] 2. Press Photography in the Context of National Socialist Propaganda Means in the Reichsgau Wartheland

[…]

2.a. Photographs as a Propaganda Means and as a Documentation Medium of Visual Propaganda Means

In the following, we will speak exclusively of German press photographs that were legally produced at the time. In the empirical findings, these can be quite clearly distinguished from other contemporaneous forms of application of photography due to the aforementioned external characteristics of the primary sources. The term “propaganda photographs” is not used in the present study. [175] As far as can be discerned, this term is usually used in the German-language secondary literature to describe photographs that positively portray a past, non-democratic state and its state ideology by means of a specific choice of motif and mode of depiction in each case. Often, different photographic genres (portraits, press photographs, art reproductions, etc.) are grouped together under the term “propaganda photography,” which is characteristic of the ambiguity and ambiguity of the term’s usage. The photographs meant by this term have not yet been precisely delimited either thematically, motivationally, or stylistically. The word “propaganda photography” was not used in the period 1939-1945; it describes the political use of photographs in the past from today’s point of view. The term propaganda photography combines the means (photography) with the function (propaganda), which should be kept apart to analyze the facts. Moreover, it should be taken into account that photographs can be not only means of propaganda, but also means of documentation of visible means of propaganda.

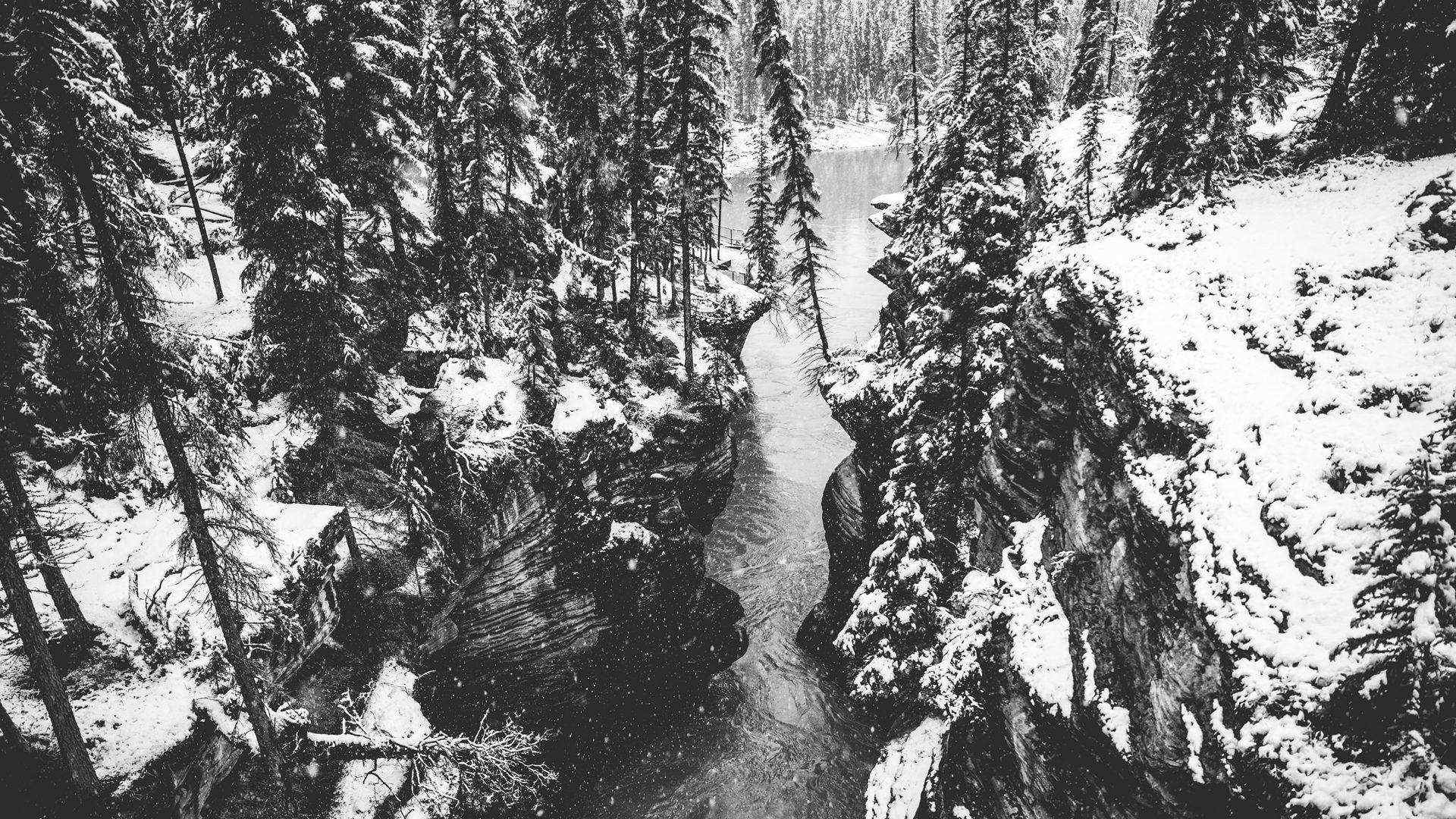

Fig. III.40: Ostdeutscher Beobachter [East German Observer] of 15.2.1942, p. 5

In the scientific German-language secondary literature, press photographs from the period of the National Socialist dictatorship have often been understood as fundamentally ambiguous images of reality, which primarily had a propagandistic function through demagogic captions, but were otherwise free of propaganda. [176] Another approach is to prove the NSDAP membership of individual German press photographers in order to explain the conformity of press photographs with National Socialist ideology. [177] Both approaches proved inadequate with respect to the empirical findings collected in the present study. Only some of the surviving photographs from the Warthegau, taken by “German” professional photographers, can be classified as ambiguous and interpreted propagandistically through image texts. [178]

The attempt to reduce the propagandistic function of National Socialist press picture propaganda to the picture captions or even to identify individual German press photographers as National Socialists did not lead to any generally valid and reliable statements about German press photographers and the functions of photography in National Socialist press propaganda in particular.

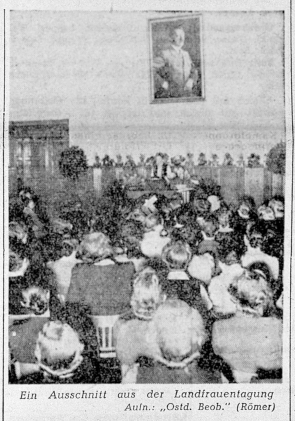

Fig. III.41: Ostdeutscher Beobachter [East German Observer], 16.2.1942, p. 3. Photographic illustration for the article “>A auch unsere Frauen helfen siegen<. First special meeting of the “Landfrauen” at the Landesbauerntag in Posen”.

The attempt to reduce the propagandistic function of National Socialist press picture propaganda to the picture captions or even to identify individual German press photographers as National Socialists did not lead to any generally valid and reliable statements about German press photographers and the functions of photography in National Socialist press propaganda in particular.

The thesis of the ambiguous photograph, which is primarily limited in its meaning to a propagandistic statement by the caption, is only partially true. A large number of press photographs in the National Socialist state were published not with demagogic, but with short informative captions about who or what is to be seen in the picture (Fig. III.39). For example, the photograph depicted here, including the surrounding captions, does not show an ambiguous visual fact that is propagandistically charged by the caption: In the foreground of the image, a uniformed man can be seen in the center shaking hands with another uniformed man in the foreground on the right. Even if there were no text attached to the photo, one could figure out by comparing it with other captioned photographs from that time and region that the man in the middle was the military district commander in Posen, General Petzel, and the man on the right was Reichsstatthalter and NSDAP Gauleiter Greiser. One may also assume that the handshake is a gesture of respectful recognition and mutual solidarity. These facts are not ambiguous.

As with the majority of all photographs, it is not possible in this case, based solely on the visual information provided, to pinpoint with absolute accuracy the time and place, or even the cause, of the symbolic interaction depicted (the mutual handshake). The time, place, and cause of the gesture can be narrowed down with relative accuracy: The visible uniforms were worn only in a certain period of time, the regionally prominent persons can be identified by comparison with other pictures, and the places where the two gentlemen shook hands can also be delimited. The caption of the picture at the time merely adds information to the photograph about the cause of the handshake: General Petzel extends congratulations. The caption of the article provides further information: General brings birthday wishes to the Reichsstatthalter. The propagandistic aspect here lies in the fact that the highest military commander on the ground in Poznan personally delivers his congratulations to the Gauleiter, which emphasizes the extraordinarily high social status of the Reichsstatthalter in the occupying society and symbolically affirms the close ties between the Wehrmacht and the NSDAP. This propaganda message did not emerge from either the photograph or the text alone, but it was created in the context of reception by the German readership at the time.

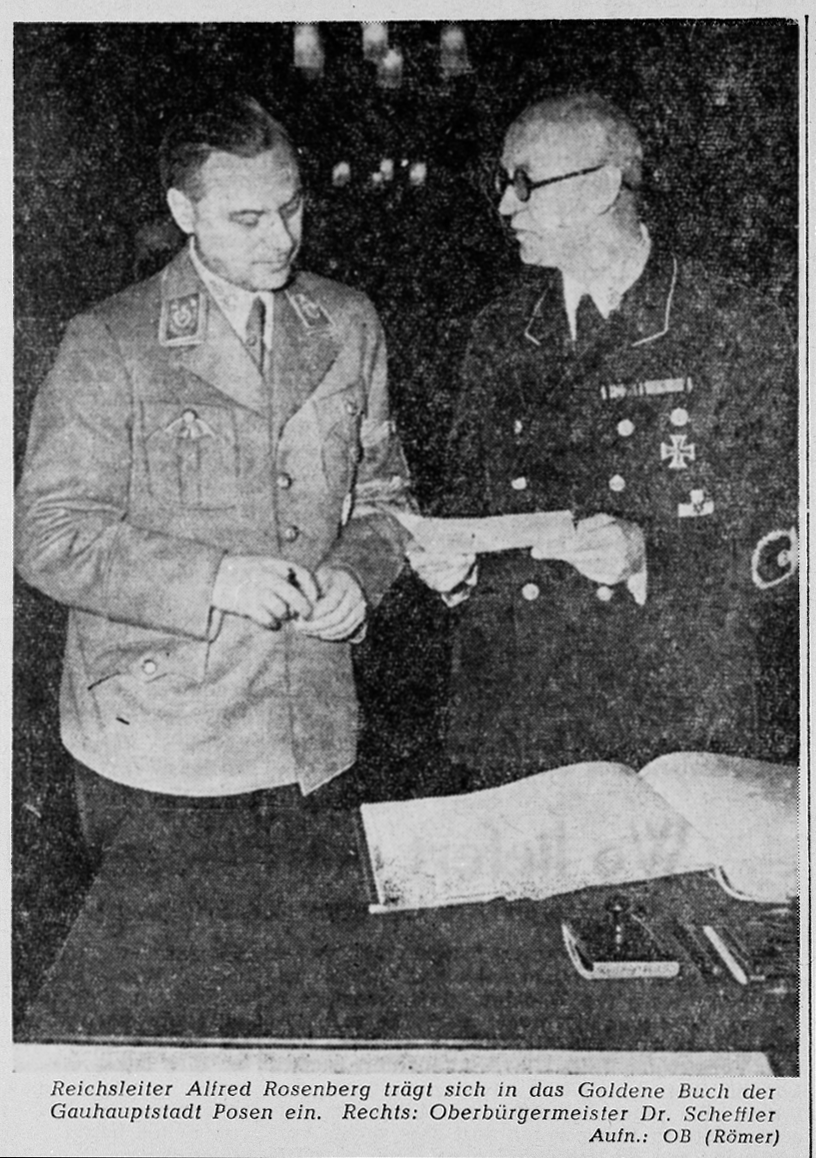

The following pages show other photo publications that served press propaganda in the Reichsgau Wartheland and for which it is also true that the thesis of the ambiguity of photography and its transformation into propaganda through picture captions does not apply. Nevertheless, these photographs are often propagandistic, since the content of the images can also convey propaganda messages (Figs. III.40-III.43).

Fig. III.42: Ostdeutscher Beobachter [East German Observer], 12.1.1943, p. 3: Photographic illustration for the article „Vorkämpfer für Großdeutschlands Sendung. On the 50th Birthday of Reichsleiter and Reichsminister Alfred Rosenberg”.

—

[175] See, for example, Sauer 2002, pp. 591f.; Jäger 2000, pp. 113-122; Sachsse 1982, p. 62; Diskussionsprotokoll AG NS-Propagandafotografie 1982, pp. 74f.

[176] See, for example, Ranke 1992. Winfried Ranke argued that propaganda began with the captioning of pictures. He writes that photographs were never used solely as a means of propaganda: The decisive factor for their propagandistic use was their subsequent captioning, and the captioning determined the interpretation of the image (pp. 64 and 72). Cf. also the completely uncritical – or better: naive – understanding of photographic image sources in EdN p. 340; here all photographs from the time of the National Socialist dictatorship are presented as “image sources” without any reference to the original propagandistic purposes of the photographic source groups mentioned.

[177] See also Ranke 1992 and the published directories of photographers by Rolf Sachsse, who has dealt very intensively with the identification of NSDAP memberships of German professional photographers – although he did not identify as such one of the most efficient suppliers of photographs for the National Socialist “Greuelpropaganda” (“atrocity propaganda”) of the war period – Karlheinz Fremke; cf. on this list of photographers here in the appendix under “Fremke” and the chapter on the “Bromberger Blutsonntag”.

[178] See in particular the examples of images discussed in the chapter “Institutional Producers of Photographs” in the section on the Deutsches Ausland-Institut.

[Excerpt: page. 226 to 229]