Page 540-544, Photographs in card indexes and collections of the Gestapo I: German Resistance

Page 540-544 > access to source at the UDK > Teilband 2 > Link

Translation of contents with the friendly permission of Verlag Dr. Kovač Hamburg.

Author information: Miriam Y. Arani

URN: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:kobv:b170-17233

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25624/kuenste-1723

ISBN: 978-3-8300-3005-8

Publisher: Verlag Dr. Kovač

Place of publishing: Hamburg

Document type: Book (Monograph)

Language: German

Year of completion: 2008

Publishing Institution: Universität der Künste Berlin

Date of release: 23.02.2022

GND keyword: Wartheland; Poland – people; Germans; photography; self-image; foreign image; Wartheland; Polen – Volk; Deutsche; Fotografie; Selbstbild; Fremdbild

Page number: 1014

License (German): No license – copyright protection

From Chapter V: Institutional producers of photographs

[…] 1. Police and photography > d. Photographs of persons for identification purposes > Photographs in card indexes and collections of the Gestapo I: German resistance

[…]

Band II. Aus: Kapitel V: Institutionelle Hersteller von Fotografien > 1. Polizei und Fotografie > d. Erkennungsdienstliche Personenfotografie > Fotografien in Karteien und Sammlungen der Gestapo I: deutscher Widerstand (540)

[Excerpt: pp. 540-544.]

Photographs in card indexes and collections of the Gestapo I: German Resistance

The previously discussed identification service photographs of persons produced by the SS and police apparatus during World War II indicate that their design was highly standardized, but by no means completely unified. This becomes even clearer if one goes beyond the production and further use of photographs by the criminal police and also includes the handling of photographs of deviant persons in the National Socialist sphere of rule by the Secret State Police and the Race and Settlement Main Office of the SS.

The various offices of the RSHA [Reich Security Main Office], including the Criminal Investigation Department and the Gestapo, were able to draw on meticulously kept, extensive card indexes, files and other compilations of material in their investigations, which often included photographs. As the political police of the National Socialist state, the Gestapo collected information and material on all “political opponents” of National Socialism in order to persecute them and, in a large number of cases, to completely destroy their existence. On January 1, 1939, the main index of the Secret State Police Office in Berlin contained about two million cards with personal data and about 650,000 associated files, to which were also attached “confidentially recorded” or “officially produced” photographs of the persons concerned. In addition, the Gestapo created special photo collections on political opponents, especially Communists and Social Democrats. [258] The collected photographs included clippings from private photographs that had been confiscated during house searches or arrests. The photographic images from the Gestapo’s card indexes, files, and special collections were used for comparison with other photographs or descriptions of persons and were presented during interrogations, sometimes in the form of entire “crimimals albums” [“Verbrecheralben”]. [259]

One “criminal album” from the point of view of the Gestapo, created during the war years in their Berlin headquarters, is the album on a German resistance group that was called the “Rote Kapelle” (“Red Orchestra”) by the Gestapo and the foreign/defense office of the OKW [Oberkommando der Wehrmacht]. [260] Behind the term “Rote Kapelle” was an oppositional network in Berlin around Harro Schulze-Boysen, a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force, and Dr. Arvid von Harnack, a national economist and senior government councillor in the Ministry of Economics. [261] In 1942, the Gestapo worked on a collection of various oppositional groups in Department IV A 2 in an investigation complex entitled “Bolshevik High and Treasonous Organizations in the Reich and in Western Europe (Red Kapelle).” These groupings were not linked by a tightly and hierarchically organized party-political organization, but formed an informal network that brought together people of socially and culturally heterogeneous backgrounds for the exchange of opinions and oppositional activities against the National Socialist dictatorship. The first contacts of this network had already formed in the first years under National Socialist rule; the loosely connected circles of friends, discussion groups and leisure communities grew together after 1939 into a larger, multifaceted oppositional network – until its violent dismantling by the Gestapo in the fall of 1942. The previous findings about the members of this resistance group, as summarized by Jürgen Danyel, show that the informal organizational network known as the “Rote Kapelle” resisted any assignment to a party-political camp. [262] It involved at least three different opposition circles, between which only loose connections existed:

– around the initially independent resistance circles around Harro Schulze-Boysen on the one hand and Arvid von Harnack on the other; the two groups did not become more closely intertwined until 1939;

– around the Legation Councilor Rudolf von Scheliha and his confidants in the German Foreign Office,

– around a network of intelligence-bases, established in Western European cities by the Polish Communist Leopold Trepper on behalf of Soviet military reconnaissance since 1938, and a circle of people in Berlin who had already been active in intelligence work for the Soviet Union before 1933.

The various groups in Berlin were linked primarily by overlapping circles of friendship in which people from different milieus came together to exchange opinions, make contact with other opponents of Hitler, help the persecuted, document violent National Socialist crimes, and distribute pamphlets calling for resistance. The motivation of those involved was based on religious or political (communist, social democratic and liberal) convictions. The oppositional tendencies in the various circles of friends around Harnack and Schulze-Boysen were triggered, among other things, by their own experiences with National Socialist violence or by a principled aversion to National Socialist ideology. In the oppositional network, free discussions of new thoughts and drafts were possible; it opened up a social free space for the participants in the face of the pressure of conformity of the National Socialist dictatorship, in which they could assert their ethical or political identity and personal integrity. In total, the ramified oppositional network of interconnected circles comprised 50 to 100 people.

Fig. V.105: Gestapo Berlin, identification service person photography of Stanislaus Wesolek, October 1942 (From: Griebel et al. 1992, p. 50)

From 1940 onward, the group around Harnack and Schulze-Boysen intensified their resistance activities and, in their search for possible cooperation partners against Hitler and the National Socialist regime, intensified their connections with illegal communist circles. Leopold Trepper sent Anatoly Gurevich to Berlin to meet Harro Schulze-Boysen in August 1941; the messages that Gurevich received from the Berlin resistance group during the conversation with Schulze-Boysen were radioed from Brussels to Moscow; therein consisted the entire “radio traffic” of the “Red Kapelle” with the Soviet Union, which later on was later embellished by the political right with numerous legends.

In the fall of 1942, the resistance group around Harnack and Schulze-Boysen was uncovered by the Gestapo and the Office of Foreign Affairs/Defense of the OKW, since the Gestapo monitored all bases of Soviet military intelligence. [263] Beginning on August 31, 1942, the Gestapo arrested more than a hundred men and women who belonged to the inner circle or wider circle of the “Rote Kapelle” in a large-scale arrest operation in Berlin. The subsequent investigation was in the hands of a special commission. The Gestapo was puzzled by the individuals it came across in its investigation of the organization, which was supposedly controlled from abroad: a ministry official, a Wehrmacht officer, many artists, and numerous women. These were groups of people whose loyalty to National Socialism they had expected. During the interrogations, those arrested declared that they had acted in responsibility for the continued existence of the German nation. Still in December 1942, a series of trials began before the Reichskriegsgericht in which more than 50 members of the Berlin resistance network were sentenced to death as “traitors to the people” [“Volksverräter”] and executed in Berlin-Plötzensee. [264]

Among those arrested was, for example, Stanislaus Wesolek (Fig. V.105), a cutter and carpenter born in Posen in 1878, who had joined the KPD in 1919 and had lived in Berlin-Kreuzberg since 1927 with his wife Frida, their three children and his parents-in-law. He was arrested by the Gestapo together with his wife and his father-in-law Emil Hübner in the apartment they shared, sentenced to death by the Reich War Court for high treason and espionage, and executed in Berlin-Plötzensee on August 5, 1943. [265]

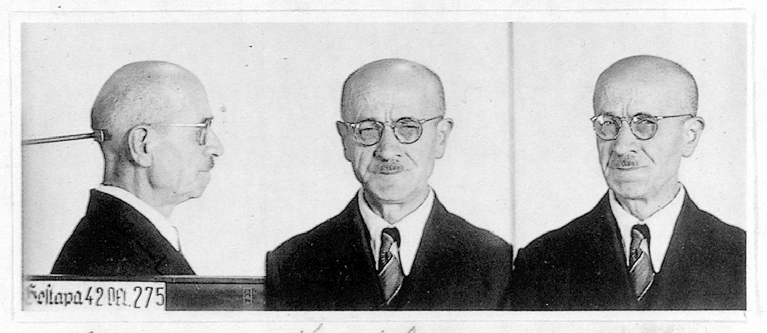

Fig. V.106: Gestapo Berlin, identification service person photography of Rudolf von Scheliha, October 1942 (From: Griebel et al. 1992, p. 46).

Also arrested was the aforementioned Legationsrat Rudolf von Scheliha (Fig. V.106). He had been born in Silesia in 1897, had enlisted as a war volunteer in 1918 after attending a grammar school. From 1919 to 1921, he studied law in Breslau (Wroclaw) and Heidelberg, stood up against anti-Semitic tendencies in German higher education as chairman of the student parliament, and took part in the Upper Silesian Uprising in May 1921. From 1922 he worked for the Foreign Office, in whose service he was finally accepted in 1924. After assignments in Prague and Turkey, Scheliha was assigned to Poland from 1932, and from the end of that year to the embassy in Warsaw. In July 1933 he joined the NSDAP, but within his large circle of acquaintances he also had many contacts with opponents of the National Socialist regime and, as an embassy employee, helped them to be released or to leave the country. From August 1939 on, he was entrusted with the “observation and combating of Polish inflammatory propaganda” in the Information Department of the Foreign Office in Berlin. Through his professional duties, he became aware of Nazi crimes in Poland and used his official leeway to support persecuted members of the Polish intelligentsia. Scheliha was temporarily head of the Information Department and, from 1941, group leader responsible for nine country departments; his own area of work was “Central, Northern, and Eastern Europe.” In 1941 and 1942 he traveled to Switzerland several times and passed on von Galen’s sermons against the euthanasia of the National Socialists; he also supported the dissemination of news about the mass murder of Jews. On Oct. 29, 1942, he was arrested in his office by the Gestapo, sentenced to death by the Reichskriegsgericht for treason on Dec. 14, 1942, and executed in Berlin-Plötzensee on Dec. 22, 1942. [266]

Fig. V.107: Gestapo Berlin, identification service photograph of Libertas Schulze-Boysen, September 1942 (From: Griebel et al. 1992, p. 11).

Harro Schulze-Boysen’s wife was also imprisoned by the Gestapo in 1942. Libertas Schulze-Boysen (Fig. V.107), who had been born in Paris in 1913, had attended a girls’ lyceum in Zurich and many European countries, and spoke several languages. She initially sympathized with National Socialism and, after working as a press officer for the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film company in Berlin, enlisted in the Reich Labor Service in 1935. After her marriage to Schulze-Boysen in 1936, she worked as a freelance writer for the theater and the press and, together with her husband, invited various guests to their shared apartment for casual conversations on cultural or philosophical topics. From 1941, she worked at the German Cultural Film Center [Deutsche Kulturfilmzentrale], which was under the Ministry of Propaganda. Here she secretly collected photographic images of German crimes in Eastern Europe, offering home leave from the Eastern Front – soldiers, officers, SS men – to develop their photographic films free of charge in the darkroom of the Kulturfilmzentrale. She secretly made duplicate prints for her own photo archive of the photographs she considered particularly meaningful. Libertas Schulze-Boysen friendly engaged the men who gave her the films in conversation, so that she also learned their names and addresses. The photographs she collected mainly concerned violent crimes against the civilian population in the Soviet Union. The secret collection of photographs with the written notes was to be used after the war to shed light on the crimes of the Nazi regime and to provide evidence for an indictment of the perpetrators. The members of Schulze-Boysen’s group showed these photos during the war, among others to young Germans who had already begun to have doubts about National Socialism, in order to make the inhumanity of this dictatorship more palpable to them. When her husband had already been arrested, Libertas Schulze-Boysen destroyed all photographs and records. She was arrested on the train on September 8, 1942, while fleeing Berlin, sentenced to death in December 1942 by the Reichskriegsgericht for high treason, favoring the enemy, and espionage, and executed in Berlin-Plötzensee on December 22, 1942. [267]

Pictured here are some of the identification photographs taken of the prisoners by the Gestapo after the arrest operation. The Gestapo filled a whole album with such photographs of persons whom they assigned to the “Rote Kapelle”. All the photographs in the album on the “Rote Kapelle” were taken at the headquarters of the Secret State Police Office [Geheimes Staatspolizeiamt] (Gestapa) – part of the RSHA – at Prinz-Albrecht-Str. 8 in Berlin, in a specially designated room. The signatures included in the picture are probably the internal signatures of the Gestapo headquarters at Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse 8. The taking of three-part photographs of the head of the person in question was part of the usual police procedure for the registration of arrested persons for identification purposes; in addition, full-figure photographs appear to have been taken while the person was standing. A comparison of the individual arrest dates with the sequence of photo numbers in the Gestapo album on the “Rote Kapelle” shows that a large number of photos were not taken immediately after the arrest, and that a large number of arrestees were photographed on individual days. The photographs taken for identification purposes were taken either when the prisoners were brought in or later in the course of their pre-trial detention on the occasion of an interrogation. [268]

—

[257] Cf. IPN-AGK Photographs on the Polen-Jugendverwahrlager Lodz. [Polish Youth Detention Camp Lodz].

[258] Coburger 1992, p. 319.

[259] Coburger 1992, pp. 318, 320f.

[260] Griebel et al. 1992. Unlike other documents, the album was not destroyed in the last days of the war by its creators, the Gestapo, themselves. It also survived the heavy air raids in April/May 1944, during which large parts of the Gestapo headquarters were destroyed, as well as a heavy bombing raid on February 3, 1945, during which the building burned out completely. The album was last located in the basement of the building, where it was found in the first days of peace; according to Coburger 1992, p. 321 with further literature references and information on the album’s tradition.

[261] Danyel 2004. The following account of the facts is based on a recent publication by Jürgen Danyel. For details, see also: Hans Coppi, Jürgen Danyel, Johannes Tuchel (eds.): Rote Kapelle im Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus. Berlin 1994. The instances of persecution in the Nazi state portrayed the Berlin resistance group as “paid traitors to the country” and as a Soviet espionage base controlled from Moscow among several others in Western Europe. The German resistance group known as the “Rote Kapelle” was surrounded by Nazi propaganda and, during the Cold War, legends of constant radio communication between Berlin and Moscow. In reality, however, radio communication failed after the group’s first attempt at radio communication due to a lack of technical knowledge on the part of those involved. There was only one several-hour conversation in August 1941 between a member of Soviet military intelligence and Harro Schulze-Boysen, in which the latter relayed information on the German fuel situation, aircraft production, chemical warfare, and the successes of German defenses. The decisive motivation for Harnack and Schulze-Boysen to pass military information to the Soviet Union had been Hitler’s plans to attack the Soviet Union; they considered victory over Hitler possible only with support from a militarily and economically strong outside power. Thus, in March 1941, Harnack had sought contact with a secretary at the Soviet embassy in Berlin, where he eventually obtained two radio sets. Since no radio messages from Berlin subsequently arrived in Moscow, the General Staff’s military intelligence service (GRU), which had bases in Western Europe, was called in.

[262] See Danyel 2004, cf. EdN, p. 705.

[263] The group around Schulze-Boysen and Harnack first came into the Gestapo’s field of vision in February 1942, prompted by a leaflet demanding the immediate evacuation of the occupied Soviet Union and a peace settlement that would preserve Germany within the borders of spring 1939.

[264] Cf. EdN, p. 705 and Friedemann Bedürftig, Lexikon Drittes Reich. Hamburg 1994. p. 301.

[265] Griebel et al. 1992, pp. 50, 234-235.

[266] Griebel et al. 1992, pp. 46, 250-251. See also: Ulrich Sahm, Rudolph von Scheliha. Ein deutscher Diplomat gegen Hitler. Munich 1990.

[267] Griebel et al. 1992, pp. 11, 66-67; Kerbs et al. 1983, pp. 197f.; Danyel 2004, p. 404.

[268] Coburger 1992, p. 318f. The full-figure photographs are not reproduced in the 1992 publication. Two such photographs are found outside the album in surviving files. Other full-figure photographs with similar picture signatures are known from the files on the resistance group Europäische Union. In September 1933, the signature “Gestapa 1 IX 1933” was assigned. In the course of the following years, the signature was slightly changed a few times by rearrangements, but retained as characteristics information on year, month and serial number. From the year 1935, among others, the signature “Gestapa 381 August 35” is known. Presumably, a new series was started after the serial number 999, because the pegboard did not allow for four-digit numbers. In one case (Walter Husemann) it is known that the “photo session” was delayed because he had attempted to jump out of the window during an interrogation, dragging an officer with him. During this suicide attempt, Husemann sustained serious injuries, with which he was left in a cell. His condition was apparently also considered unsuitable for a Gestapo photograph. Coburger 1992, p. 319.

[Pages 540-544.]